Our Moment on Earth – Part III

by Usha Aexander

[This is the seventh in a series of essays, On Climate Truth and Fiction, in which I raise questions about environmental distress, the human experience, and storytelling. It first appeared on 3 Quarks Daily. This seventh essay is divided into three parts. Part II is here. The sixth essay in the series, called “Modern Myths of Human Power”, is here.]

Turning the Page

As I’ve discussed in previous essays in this series, after the last glacial age loosened its grip and the climate regime stabilized into the Holocene, many of our ancestors were pursuing new, previously inconceivable experiments in living, with more and more of them settling down and starting to farm. As their populations mushroomed, they forgot the stories they once told about wandering the unstable Earth and living in its uncertain mercy. In the new stories that arose, gods favored human beings over all other creatures, and favored some individuals and classes of people above others. Grasping more tightly to places and things became virtuous. Those who embraced these new values took the most and grew the fastest. As their hunger for energy and resources outstripped every land they conquered, as the hungriest came most mightily into competition with one another, the rapidly mounting technologies and narratives for greater extraction and subjugation – of land, animals, and people – played no small part in one’s advantage over another.

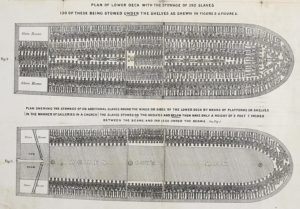

Fossil fuels are the most concentrated, transportable, and easily harnessed energy source humans have ever found. As we became more adept with them, extracting, consuming, and growing also became easier and faster, ushering in an Industrial Age of previously inconceivable bounty and leisure for some, while holding out its promise for others who might also climb aboard the juggernaut. Almost at once, the human population skyrocketed. The biosphere around us began to visibly decline. But few found cause for concern. Quite the contrary: plundering more and more of the Earth and its biome, without recompense or regard, came to be seen as clever, if not a divine destiny of humankind; it’s what the almighty Invisible Hand required. The solidifying nation-states of Europe competed with each other to subsume the globe, to stamp it with their presence and direct its destiny toward their maw. As this historical process unfolded, and every corner of the Earth fell subject to the directives of growth economics, we started telling newer stories about our godlike potential, about order and progress and boundless power. Stories of limitless growth.

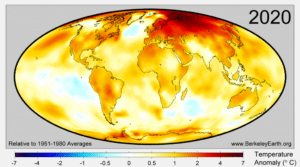

Today we must ask, what will we do next? What stories will we tell? If we can no longer ignore the collapse of the biosphere and the changing of the climate, how will we then re-conceive our relationship to the planet, to wilderness, to extraction and consumption and subjugation, and the real limits of the Earth system we inhabit? If we don’t question the very narratives that brought us to this brink, we’ll not discover new ones that can help us change the way we live. It’s now patently clear that the way we live is not sustainable and therefore must change. The stories that led us here have brought us to a dead end.

I am no luddite typing this on my sleek computer, posting it on the World Wide Web. I know that I have benefited as much as anyone – more than most – from the gee-whiz world in which I came of age. More than that, I understand technology as an essential and inevitable product of our humanity. But, given its concomitant damages, neither do I see it as unreasonable to wonder at the way the technological world has borne out. It will be wise to take seriously those regularly beaten-down questions about scale, purpose, harms, costs, and who benefits from any given innovation – rather than maintain our resolute allegiance to the narrow forces that regard all human interventions in nature and every possible satiation of human desire as good, necessary, or unavoidable, because it feeds the Market and furthers the fortunes of the already fortunate. Though our creed of growth as a virtue and progress as divine destiny has led us to astounding feats of medicine, scientific understanding, and technological power, it reveals itself a Faustian covenant. These gifts have come at the cost of destabilizing our world to a degree that they are yet powerless to set right. The myths and modes of thought and action that brought us to this moment on Earth no longer promote a genuine promise of wellbeing into the future. More of the same will not solve the problem it created.

In the West today, growth economics has been conflated with democracy itself – strategically by the oligarchs and their proxies, lazily by the general public – so that anyone who dares to point out that economies of growth are leading us toward an existential dead end is branded a Communist, a Luddite, a freedom-hater, or worse. Yet, we must acknowledge that the human enterprise has reduced the Earth’s plant biomass by half since the dawn of agriculture; plants make up about eighty percent of total global biomass. And as of 2020, for the first time ever, our artificially built world – all the asphalt and concrete and machines and plumbing and plastic currently in use – now outweigh all the world’s biomass – every mushroom and microbe and mammal, every tree and grass blade and bird. Each week, anthropogenic mass equivalent to the bodyweight of every living person is continuously produced. This excludes our trash – and our carbon emissions. Having now already supplanted a once densely diverse biome with the monocultures of human bodies and human food species, having already produced enough waste to upset the very biological and geochemical systems that have thus far sustained us, we are demonstrably at the end of any viable growth trajectory – if not already in a state of overshoot. Stories of growth and unboundedness are crashing against any dreams we might have of sustainable human thriving. Yet we currently have no newly ascendant narrative competing for our collective mindshare to help us construct a sustainable future. So far, we have only the old narratives, nicely spiffed up in fashionable new green garb. Green products. Green consumerism. Green tech. Green growth.

Most of the “solutions” that the powerful factions of the world recommend to answer anthropogenic climate change seem to have been envisioned with the intention of preserving global civilization just as we know it: All of the extant power differentials and disparities of wealth. All of our current geopolitics. All of our present forms of prosperity and disparities of wealth. All our pleasures of consumption and convenience. All our hubris. All of our illusions about extraction and growth, power and control. All our voluptuously glided stories that have guided us toward catastrophic system failure.

But our artificial world, as presently conceived and built, is not sustainable and will not magically be sustained by pulling fresh “green” levers of extraction and growth, whatever those levers may be. And either way, it bears asking, how much of our present world is worth preserving? When we speak about building a sustainable world, what exactly is it that we’re hoping to sustain? If we have to choose between one thing and another, what are we willing to let go of? What is worth jettisoning for the realization of a greater good? Under a situation of faltering agriculture, farm animal heat stress, and die-offs, declining marine stocks, changing landscapes, shrinking glaciers and depleting aquifers, and mass migration – all conditions which have already been locally realized in some parts of the world and which will manifest across larger areas over the coming decades – what can we hope to create in place of that which is breaking down?

I want to ask about transformation. We live now at a moment when circumstances conspire to remind us that we live within illusion built upon illusion as the planet metamorphoses beneath our feet and over our heads. Though most of us have forgotten our oldest stories, it yet remains true that we dwell in the mercy of the sun and wind and rain. The one thing that becomes clearer in surveying the human story up till now is that recognizing ourselves as a part of nature – rather than separate from it – is essential to a sustainable and resilient lifestyle. Considering everything we know of the past and present, everything we know of human possibility, what is the best vision we can strive for?

Meeting the goal of a sustainable civilization on Earth is not merely a technical problem we humans face, as it is usually framed in mainstream discourse. In order to get there, we need to be able to richly and unflinchingly imagine the possible futures that await us, based on our best scientific understanding. Only by peering into the darkness might we discover new conceptions of hope and possibility. We need to confront and interrogate the dominant narratives that are failing to help us meet our moment on Earth. And we must begin to dream new ones.

[End of Part III]

Usha Alexander was born to Indian immigrants who came to the United States in the 1950s and settled in the very small town of Pocatello, Idaho. She ran away to university at the age of 19, and later joined the US Peace Corps, where she served as a science teacher in the archipelago nation of Vanuatu. In the late 90s, Usha made her way to the San Francisco Bay Area of California, where she settled and worked for Apple Computer for many years.

Since 2013, Usha resides with her partner, writer and photographer, Namit Arora, in the National Capital Region of India. Usha has lived in four different countries and has learned to carry her home within herself, yet she frequently returns to the CA Bay Area with a certain sense of homecoming.