Modern Myths of Human Power – Part III

by Usha Alexander

Deposing the Gods

In our contemporary superhero realms, the greatest threats against the world are supervillains, often recognizable as a mythic archetype called the Trickster. These kinds of supervillains personify chaos, or – as Americans often like to call it, with their penchant for the binary – evil. Supervillain Tricksters possesses overwhelming power that cannot be harnessed into the service of our military, other technologies, or government. Blockbuster stories give us, for example, The Joker (stunningly rendered as chaos by Heath Ledger in The Dark Knight of the DC Universe (2008), who hounds our brooding anti-superhero, Batman. The Marvel Universe borrows Loki, the exemplanary Trickster, straight from Norse mythology, and introduces Dormammu, Lord of the Dark Dimension, who exists outside of human time, as among the great threats to human-imposed order.

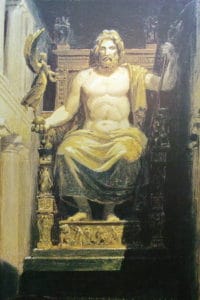

In the ancient stories, the gods themselves were often Tricksters. Even those who didn’t specialize as Tricksters – as Loki did – behaved according to their own whims, unbound by human moral codes or social responsibilities. Like modern Trickster supervillains, we often see the gods working against the hero or the greater human good, depending upon their Mercurial moods and inscrutable intentions. In Greece, for example, however much Athena adored Odysseus, she just couldn’t be bothered to help him overcome the vicious obstacles that Zeus and Poseiden placed against his homeward journey. In South Asia, Krishna incited a great war between the Pandava brothers and their cousins, the Kauravas, deftly playing one side against the other and then goading Arjuna to undertake a battle that will annihilate the world. In Mesopotamia, the gods went so far as to destroy civilization with a flood that scoured all life from the planet, sparing only a handful of individuals upon a boat, which a rogue god had instructed them to build. Mayan and Polynesian gods destroyed civilization multiple times in equally colorful ways.

But in Bronze and Iron Age tales, the heroes were still dependent upon these capricious gods. Heroes had to learn how to properly worship them in order to curry their favor or convince them not to destroy civilization again. The ancient hero’s goal was never to defeat the tricky gods, but to beg their mercy or request their help and advice in the attainment of very worldly and often ignoble aims. Ancient heroes asked favors from the gods to win battles, trick their rivals, and cheat death. Sometimes the gods refused these requests or even answered them with trials and travails. But that was the perogative of gods; it didn’t make them the enemy, and even the heroes knew their place in the order of things.

Through the stories of Bronze and Iron age agriculturalists demonstrate that their folk surely were enamored of the macho worlds they had already built, still their stories retain some sense of limit or proportion, in which human deeds and desires belong to a larger sum of things, rather than being the measure of all things. For them, the gods still set the conditions to which humans were subject. Their gods – representatives of powerful nature, an amoral universe, the cosmic chaos with which humankind was challenged to find a workable amity – were always greater than us, more powerful and wiser, even in their inconstancy. Ours was not to question why.

In our 21st century superhero stories, by contrast, the power dynamic between humankind and Trickster-kind has decidedly shifted: Tricksters have become the enemy. We no longer see any need to placate them; rather, in service to humanity, we must remove them, annihilate that which we cannot command, and accept no limits upon our powers or our sense of human destiny. Humans are the godlike beings in this formulation, while the formerly godlike Tricksters have been cast out as villains.

Thus Spake the Avengers

Our contemporary stories celebrate human power that is unbounded by nature. We expect science and technology to solve every problem we might face, without limit (even those who openly dismiss science in favor of religion or politics operate with this expectation, apparently without even being aware of it). These are foundational presumptions of our modern cosmology, reflected as much in our popular myths as on the ground. As we destroy unruly nature, forcing it to conform to modern human notions of order and predictability in agribusiness, in nature tourism, in urbanization. As we torture sentient beings in factory farms or “efficiently’ trawl the oceans to blithely slaughter vast villions of creatures every year. As we casually raze wilderness and forests to install monocultures or to build concrete cities containing neatly delineated spaces for grass and flower beds. It’s in our adamant denial of natural limits to sustainable human endeavors – of commerce, industry, consumption, growth – a willful illusion that propels our pillaging of this planet and obscures the need to change course.

In the Avengers storyline, Thanos warn humanity about the suffering that results from overpopulation. But in the films, no character is touched by want or deprivation in any way. And the only threats we see to universal peace are from Thanos himself and his minions. By never allowing the possibility of suffering to be seen as real, the storytellers cast Thanos as a false prophet and a genocidal monster. And after he is deposed, the previous status quo is triumphantly restored. Thanos, the god of death, of existential finitude, is the enemy of the people of the modern world, who have been weaned on paradigms of endless growth, myths of unbounded human power, and ideological optimism in the face of all obstacles and limits. It takes little to see how such popularly resonant stories of ourselves blind us to the true precariousness of our present human predicament. Such stories of unlimited human power have not only played their part in chaperoning us to this moment, but may yet inhibit our ability to imagine how best to respond to our present global crisis. Rather than showing us the way forward, they will likely deepen our plight.

[End of Part III]

[Modern Myths of Human Power – Part I]

[Modern Myths of Human Power – Part II]

Usha Alexander was born to Indian immigrants who came to the United States in the 1950s and settled in the very small town of Pocatello, Idaho. She ran away to university at the age of 19, and later joined the US Peace Corps, where she served as a science teacher in the archipelago nation of Vanuatu. In the late 90s, Usha made her way to the San Francisco Bay Area of California, where she settled and worked for Apple Computer for many years.

Since 2013, Usha resides with her partner, writer and photographer, Namit Arora, in the National Capital Region of India. Usha has lived in four different countries and has learned to carry her home within herself, yet she frequently returns to the CA Bay Area with a certain sense of homecoming.